HISTORY

ASIFA-HOLLYWOOD’S FIRST FIFTY (OR SO) YEARS

By Michael Mallory

OVER THE COURSE OF FIVE DECADES ASIFA-Hollywood has dedicated itself to being one of the premiere organizations in the world promoting the art and industry of animation…but that’s only the beginning of the story. From its inception in the early 1960s, ASIFA-Hollywood has managed to set trends and establish institutions, and even launch an industry or two. Animation cels were not considered collectible art until ASIFA-Hollywood began to offer them for sale to the public. Awards were given to animation only on a token basis until the creation of the Annie Awards. Both of these innovations were the creations of the guiding force of ASIFA-Hollywood, June Foray. But there is so much more to ASIFA-Hollywood’s story: historic screenings and presentations; classes; AniFest; the Animation Opportunities Expo; the Animation Archive; and publications such as The Inbetweener and Grafitti, just to name a few of our more visible activities. The list of people who have been involved with ASIFA-Hollywood is a virtual who’s who: June Foray, Bill Scott, Steven Bosustow, Ward Kimball, Frank and Ollie, Chuck Jones, Mark Hamill, Gary Owens, Bill Littlejohn, Roy Disney, Tom Kenny, Seth Green, Stan Lee…even William Shatner and Phyllis Diller!

WANT TO KNOW MORE ABOUT ASIFA-Hollywood; who we are, what we’ve done, and what we’re continuing to do? Check out the story below and become part of the excitement!

-

For close to half a century ASIFA-Hollywood has been the little train that not only could, but did, standing alone in its mission to recognize, foster and promote the art and industry of animation. From its beginnings in the early-1960s as a screening society to its present incarnation as the purveyor of the Annie Awards, the most prestigious award dedicated to the animation, and its ongoing establishment of the world’s most complete and comprehensive archive of animation materials and history, ASIFA-Hollywood remains the animation industry’s most proactive organization. The International Animated Film Society, ASIFA-Hollywood, is one of the longest-operating chapter of ASIFA (Association Internationale du Film d’Animation), an organization that was created in Annecy, France in 1957, and chartered under UNESCO as an advocacy and education organization in 1960. ASIFA-Hollywood was created only a few years later by a group of animation professionals that included producer Les Goldman; animator Bill Littlejohn, who was then vice president of ASIFA; actress June Foray, renowned as the voice of “Rocky the Flying Squirrel;” Ward Kimball, one of Disney’s fabled “Nine Old Men;” British animation artist John Wilson, then working at Hanna-Barbera; animator Carl Bell, who worked with Goldman at Sib Tower 12 Productions; and cinema professor Herbert Kasower. Many within this group had been to the Annecy, France, Film Festival, a then-young event sponsored by ASIFA, and were looking for ways to bring the films they had seen to an American audience.

“There was this noble intention of bringing over these films from the European studios, like Zagreb, which were quite different in style, stories and graphics to anything that was being done in Hollywood,” says Carl Bell. “It was a way to stimulate the animation artists in Southern California and show there were other ways to make animated films.”

Goldman, Littlejohn, Foray, Bell, Wilson, Kasower and Kimball—along with his son John, who was also an animation artist—would comprise the nucleus of what was originally called “ASIFA West Coast.” Once word got out about the fledgling organization, the core nucleus quickly expanded. Among the first wave of members were William T. Hurtz, Bill Scott, Stephen Bosustow and his son Nick Bosustow, Barrie Nelson and Rosalind (Merrifield) Nelson, Fini Littlejohn, Bernard Gruver, Leo Salkin, Jules Engel, Adrian “Ade” Woolery, Herb Klynn, Spencer Peel, and Hannah Cannon (the daughter of Bobe). Hurtz, Gruver, Goldman, both Bosustows, Scott and Salkin would go on to serve as presidents. The first ASIFA West Coast meeting was held in home of the late animator Bobe Cannon. Subsequent meetings would be held either restaurants, such as the Hollywood Brown Derby, or office buildings, such as the Vine Street Tower.

Initially, the organization was formed with the purpose of making available for exhibition foreign animated films that otherwise would never be seen in the United States. To this end the organization joined forces with Los Angeles County Museum of Art curator Henry Hopkins, who had established the museum’s education department. “The L.A. County Museum had a big theatre, but it was not designed for film,” recalls Bill Littlejohn. “It was for operas, concerns and music. When John Wilson approached Henry Hopkins about doing a show there, Henry said: ‘But we don’t have a screen.’ Well, John got a big bed sheet…literally! The first show we put on at the County Museum, we showed 16mm projected onto an improvised bed sheet, and it worked fine. The people came in and they didn’t give a damn about a bed sheet. It was the content.”

It was in this endeavor that the contribution of Herb Kasower, the only founding member that was not a working animation professional, proved to be invaluable to the fledgling organization. “Because he was a professor at USC, a non-profit organization, he was able to bring in all of the films for screenings from Europe without paying duty,” Bell says. “If it was, say, MGM Animation, the tax people at the airport would be there saying, ‘Where are you screening? How much money are you getting for it?’ But since it came in as a non-profit, there were no taxes on it.”

The ongoing program of international animated films eventually became the Tourneé of Animation. When Kasower, who also served as ASIFA West Coast’s first president, died tragically young from a form of cancer, the task of setting up Tourneé screenings was taken over by Philip Chamberlin, who worked at the Motion Picture Academy.

All of ASIFA-Hollywood’s founding and charter members were hardworking and dedicated to the cause, but the individual who would have the most lasting impact on the organization and through it the animation industry in general was June Foray. Foray held the office as president from 1973 to 1979, and prior to that, she was a very active board member who, among other duties and activities, wrote and edited the organization’s newsletter. At that time the newsletter did not carry a name, though it would eventually become the quarterly publication “Graffiti,” which in its early days was edited by Bill Scott. Beginning in the early 1980s, a monthly newsletter called “The In-Betweener” was launched, and it ran (with and without the hyphen in the title) for more than a decade.

In 1972 board discussions turned to finding ways to raise funds, and Foray had a revolutionary suggestion: hold an open sale of animation cels as frameable art. “I thought people would like that, maybe for their little kids, to hang on the wall,” she says.

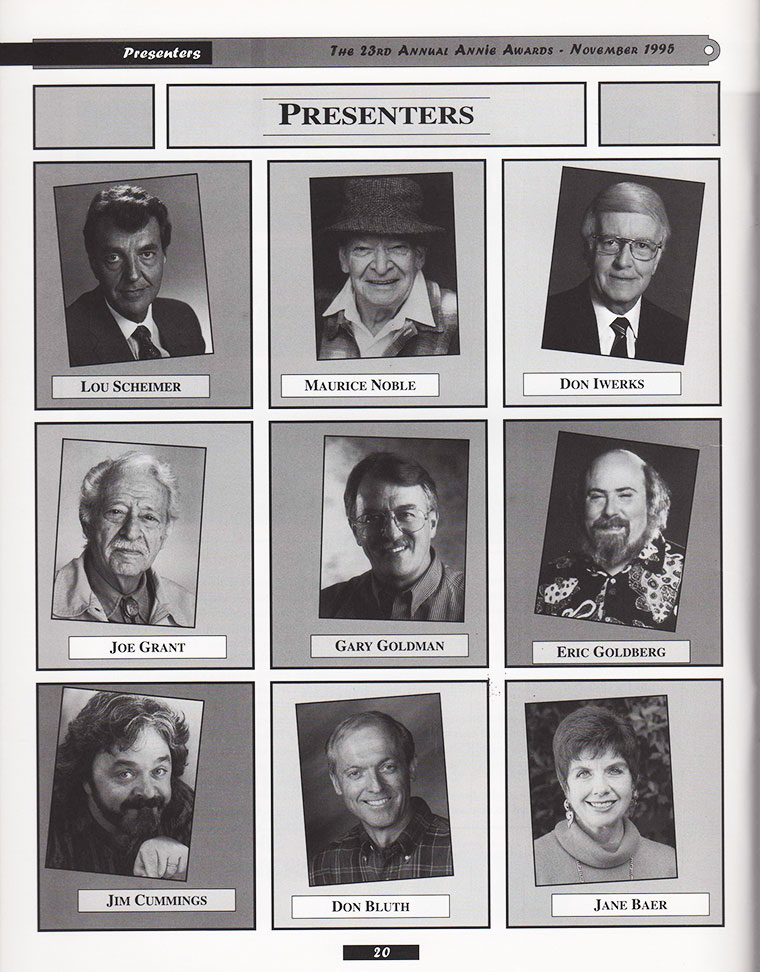

Presenters of the 23rd Annual Annie Awards – November 1998 After obtaining donations of production cels for theatrical films, television shows and commercials from Hollywood animation studios, Foray opened the doors of the San Fernando Valley home she shared with her husband, producer Hobart Donavan, to the general public and the animation industry alike. Among those present that August afternoon in 1972 for the first cel sale were Ray Bradbury, Chuck Jones, and announcer/voice actor Gary Owens. “Everybody who was anybody in animation came, and nobody fell in the pool!” Foray recalls with a laugh.

The sale was an enormous success, netting some $5,000 for ASIFA West Coast, and setting the standard for yearly fundraising cel sales that would continue for decades, though only the next one or two of them were held at the Foray’s house; after that they were held in shopping malls.

June Foray had yet another great idea in 1972: holding a dinner that would honor veterans of the animation industry, starting with the Fleischer brothers, Max and Dave, whose studio in the 1930s had been considered the chief rival to Walt Disney, but who by the 1970s were both out of the business and semi-forgotten. Max, who had run the studio, had died shortly before, but Dave, who directed many of the studio’s films, was still alive, and Foray had gotten to know him.

Even though some on the ASIFA-Hollywood board of directors were skeptical that such an event would be supported by the industry, organization began for the banquet, which would be attended by guest-of-honor Dave Fleischer and film director Richard Fleischer, who was Max’s son. Animator Grim Natwick, who had been a key creative force at the Fleischer studio, was to be the speaker for the evening. Despite the earlier fears, more than four hundred people showed up to the event held at the Sportsmen’s Lodge restaurant in Studio City, where they were regaled by Natwick’s wit. (Years later, in 1990, Natwick himself was feted on the occasion of his 100th birthday; it remains one of the most fondly remembered of all ASIFA-Hollywood events.)

With that first banquet, held in November 1972, not only was a tradition born, but a name as well. “I called it the Animation Award,” Foray recalls,” and then my husband said: ‘Why don’t you call it the Annies?’”

The organization itself underwent a name change in 1974, after Foray had taken over the presidency. “When June came in, we decided to change the name to ASIFA- Hollywood,” says Rosalind Merrifield Nelson, who was then actively involved in the organization. The new moniker came in part because a sister ASIFA chapter was opening in San Francisco, which was also on the West Coast. Since the establishment of that chapter entailed getting ASIFA to amend its rules and allow more than one chapter per country, clear definitions between the two California chapters were sought. Perhaps more importantly, though, the change served to chart the organization’s shift to nonprofit status.

“We were starting to make money,” Foray recalls,” and Roz Merrifield said, ‘I’ve got a good attorney, let’s get it done. So we went to her attorney and I don’t think he charged us very much, if anything, and we became nonprofit. That was extremely important because we weren’t there to make money for our own preservation. It was for the preservation of animation.”

The second Annie Awards were held later that year, with Walter Lantz, the creator of Woody Woodpecker, designated as the guest of honor. 1973 proved to be the only year in which only one Annie was presented. Nineteen seventy-four saw the creation of a new Annie tradition: the Winsor McCay Award for Lifetime Achievement in Animation. Named after pioneering newspaper comic strip artist and animator Winsor McCay, whose creation of “Gertie the Dinosaur” in 1914 is widely regarded as the first emergence of personality animation, the award was designed to honor individuals who had worked primarily as animators, as opposed to story, layout or design artists, or directors, actors and producers. Former Disney animator Art Babbitt was the first recipient of the Winsor McCay Award, though that year’s other Annie recipients were hardly slouches: cartoon masters Tex Avery, Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng!

The mission statement and goals they came up with continue to guide ASIFA-Hollywood’s activities today:

- To support and encourage animation education

- To support the preservation and critical evaluation of animation history

- To recognize the achievement of excellence in the art and industry of animation

- To increase public awareness of animation

- To act as a liaison to encourage the free exchange of ideas within the animation community

- To encourage journalism documenting current trends and activities in animation

- To encourage the social interaction of professional and non-professional animation enthusiasts

- To encourage the development and expression of all forms of animation

Goal number two on that list became an official function of ASIFA-Hollywood in 1991 with the creation of the Animation Preservation Project, which raised funds to transfer rare cartoons from unstable nitrate film stock to acetate stock, thus ensuring the films would be around to be enjoyed and studied for generations to come. Project Director and former ASIFA-Hollywood board member Jere Guldin, in a partnership with the UCLA Film and Television Archive, have saved such early works as 1916’s I’m Insured; Old King Cole; a 1926 silhouette short promoting Easter Seals; two Oswald Rabbit cartoons: 1928’s Farmyard Follies (produced for Universal by Walt Disney) and 1933’s Confidence; a 1930 Toby the Pup cartoon Circus Time, which was once thought lost forever; the 1931 Flip the Frog cartoon Flying Fists, from Ub Iwerks; and Scrappy’s Puppet Theatre, a Columbia promotional cartoon from 1938.

Up until 1992, the Annie Awards were handed out for cumulative career achievement, but Manoogian wanted to transform the event into something resembling established Hollywood awards shows, such as the Oscars® and the Emmys. Things started small: the first round of competitive categories were for Best Animated Feature, Best Television Program, and Best Animated Television Commercial. In addition, three Individual Achievement Annies and three Winsor McCay Awards, which would now recognize lifetime achievements, were given out. Within a couple years the program had expanded to include Home Video Release, Voice Acting, and more general artistic achievement categories, such as “Individual Achievement for Creative Supervision” and “Individual Achievement for Story Contribution.” By the mid-1990s, though, the number of categories increased and became more specialized, with Annies being presented for Production Design, Music, Writing, Producing, Storyboarding and Directing.

One of the most important additions to the roster of Annie Awards presented each year came in 1995 with the creation of the June Foray Award, given to those whose involvement in animation has made a positive and significant impact on the industry and the art form. Since no one has done that more so than June Foray herself, she was the award’s first recipient.

Even with an ASIFA-Hollywood event going on virtually every month of the year, the Annies remained its biggest production of any given year. During the event’s transitional years of the 1990s, the Annies remained a unique evening wherein any ASIFA-Hollywood member could show up and rub elbows with such industry giants as Marc Davis, Chuck Jones and Bill Hanna. For many people the party as much a reason to attend as the actual award ceremony. But the drive to make the event bigger, and increasing financial support via sponsorships from studios and production companies, allowed the Annies to grow exponentially by the year, which meant that the original venues were quickly outgrown.

More than anyone, longtime ASIFA-Hollywood member Chris Craig presided over the transition of Annies, staging the shows in the early years and continuing to be a key member of the production team to the present day. In 1996 the Annies moved out of the Television Academy Plaza Theater in North Hollywood and into the spacious Pasadena Civic Auditorium, which earlier that same year had housed the Emmy Awards. After only two years the Annies moved again, this time to the historic Alex Theater in Glendale, from where it was filmed for television airing in 1999, to date, the only time the Annies have been televised. Then in 2008, the Annies moved again, this time to the theater in Royce Hall at UCLA.

Over the course of twenty years, what was once a small, niche industry event—important, to be sure, yet somewhat separated from the motion picture industry at large—has blossomed into one of the most professional awards shows in Hollywood. This sentiment was expressed by Marvel Comics legend Stan Lee, who was an Annie presenter in recent years. Before getting to his scripted lines, Lee ad-libbed: “The other big Hollywood awards shows could learn a thing or two from the Annies!” The fact that such established stars as William Shatner, Jason Alexander, Fred Willard, Phyllis Diller, John Ratzenberger, John Leguizamo, Lisa Loeb, Rene Auberjonois have graced the Annie stage as presenters, is a testament to its position as a major Hollywood awards ceremony.

Outside of the Annies, ASIFA-Hollywood moved into its first dedicated home in the organization’s three-decade life: the ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Center in Burbank, which opened its doors March 26, 1993. Prior to that ASIFA had occupied a series of temporary offices all over the map of Los Angeles, but with the establishment of more permanent digs the organization was able to offer a wide variety of programs to its members. These included screenings, gallery exhibits, filmmaker forums, and classes. ASIFA-Hollywood remained headquartered in the Animation Center for more than a decade before moving to a new, larger Burbank location.

Outside of the Annies, ASIFA-Hollywood moved into its first dedicated home in the organization’s three-decade life: the ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Center in Burbank, which opened its doors March 26, 1993. Prior to that ASIFA had occupied a series of temporary offices all over the map of Los Angeles, but with the establishment of more permanent digs the organization was able to offer a wide variety of programs to its members. These included screenings, gallery exhibits, filmmaker forums, and classes. ASIFA-Hollywood remained headquartered in the Animation Center for more than a decade before moving to a new, larger Burbank location.Something else that had become much larger was the Animation Art Festival, the yearly even that had grown out of the cel sales. Just as the Annies quickly outgrew their initial banquet setting, this event had become so popular that before long it moved into the Woodland Hills Promenade shopping mall. Then-board member Ron Stark is given the credit for pushing the cel sales to the next level in a more public venue. What is considered the first official Animation Art Festival was held in 1983. In addition to the cels from various studios up for sale, June Foray and Bill Scott delighted audiences by performing a live Rocky and Bullwinkle script, and animation artists gave drawing demonstrations. Within a few years the venue changed again, this time to the Sherman Oaks Galleria, and the guest artist participation became more notable.

“There were people who, through the years, participated as they were available, like Hans [“Snidely Whiplash”] Conried,” says Ross Iwamoto, who coordinated the event for several years. “For instance, we sold drawings Chuck Jones did for $35. He would ask you what you wanted and then you picked the character. It was the same with Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston.”

Today, the thought of a time and place wherein anyone could show up and buy a Chuck Jones, Frank Thomas or Ollie Johnston original for $35 is enough to make one want to build a Wayback Machine, and even at the time, many took advantage of the opportunity. Among the eager young animation fans and students whose entrée into ASIFA-Hollywood came through these events are Manoogian and longtime board members Stephen Worth and Bill Turner, all of whom would go on to receive June Foray Awards. “It was so wonderful that all these well-known people participated, animators and voice artists,” says Iwamoto. “Everybody was so generous, because they donated their time for this.”

By 1993 the Animation Art Festival had grown to its peak and was rechristened AniFest. It included celebrity appearances, panels with animation professionals, promotional displays showing upcoming animated products, staged readings of cartoon scripts, and dealer tables for toy and memorabilia. Eventually the event cycled down due in part to the fact that by the end of the 1990s many of the major studios themselves had started up their own animation art businesses, specializing in limited edition cels. “The animation art market just wasn’t there any longer to make it worthwhile to do the event,” says Manoogian, who notes that the heyday of the Animation Art Festival took place “in the days before animation artwork was the hot collectible.” It can certainly be argued that Foray’s fundraising idea and two decades of successful cel sales by ASIFA-Hollywood is what created the animation art industry in the first place.

Yet another major industry event was launched in March of 1994: the Animation Opportunities Expo, which was created in response to the beginning of the so-called “Toon Boom,” the major resurgence in animation in Hollywood. “I kept hearing people say, ‘Oh, I’m taking my portfolio here,’ or ‘I’m dropping it off there,’ and there seemed to be a lot of activity going on at all these studios,” Manoogian recalls. “I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to bring everybody under one roof, so you could spend a day and shop your portfolio around?’” As a way of bringing together talent with studios who were then hungry for it, that first Animation Opportunities Expo, held at the Beverly Garland Hotel in North Hollywood, was a huge success. By the second year, seminars with animation professionals were part of the package, and when it outgrew the Garland, the event moved into Glendale Civic Auditorium, where it was transformed into more of a trade show for animation. The last two Expos were staged in conjunction with the World Animation Celebration, held in Southern California.

In 1998 the ASIFA-HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION AID FOUNDATION was formed as a California non-profit corporation for the charitable purpose of providing relief to members of the animation community who have encountered catastrophic or disaster losses. To date, several members have been helped through donations and auctions. The foundation is qualified under Internal Revenue Code Section 501(c) (3). Subject to applicable law, gifts to ASIFA-HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION AID FOUNDATION may be deductible to the donor as a charitable contribution under Section 170 of the Internal Revenue Code.

Khuma Crew ASIFA-Hollywood continues to honor its founding goal by presenting films and film makers from around the world to its members. Recent screenings have included Waltz with Bashir, Persepolis, Secret of Kells and many others. Often these screenings are followed by a Q & A with the film makers moderated by ASIFA-Hollywood board member Jerry Beck. Beck has also screened for members hundreds of rare films from his own collection of classic American cartoons. Tom Sito, vice president of ASIFA-Hollywood since 1992, created a series of “Evenings With” where he interviewed past masters like Joe Grant, Dave Tendlar, Bill Melendez and Maurice Noble. In 1990 he organized the 100th birthday banquet for Betty Boop creator Grim Natwick, which became the last great gathering of the legendary artists from Hollywood’s golden era. He has also created a 50th anniversary reunion picnic for the original Disney Studio strikers, as well as anniversary reunions of artists and creators of The Little Mermaid and The Iron Giant.

In 2008, educators on the board of ASIFA-Hollywood established an Animation Educator’s Forum (AEF) in order to begin a dialogue and share information with all those who teach animation. Since its inception, the AEF has created a successful Student Film Festival, a retrospective of educators personal films entitled “Those Who Teach- Do!”, and has launched a new interactive website to suit the needs of animation instructors.

The Animation Educator’s Forum is dedicated to the preservation and promotion of animation through education. Our members, with their diverse backgrounds in both the animation and educational fields, are focused on extending their knowledge and experience to others within the burgeoning animation community, worldwide.

There is no question that ASIFA-Hollywood has grown remarkably in its first five decades, but there is equally no question that it will continue to grow and prosper in the coming years.

For those dedicated the art and industry of animation, the best is undoubtedly yet to come.